With a rental car and vague directions in Franglais, dodging the Marrakechi drivers, we made our way north. A near-accident in a roundabout and we found the highway, N9, wide and smooth, relatively empty. The surroundings were all black and red rocks, Martian, strange and sharp and dangerous-looking formations. We transferred to A7 and saw a uniformed policeman standing on the shoulder, hitchhiking.

The farther north we got, the smaller the country roads, two lanes filled with cars eager to pass each other, donkey-pulled carts, mopeds, 3-wheelers, people riding donkeys sidesaddle, people waiting to cross, poised to dart in front of your car if you don’t speed up.

Men and children grazed animals (sheep, cows, donkeys, goats, horses) in fields on the sides of the road and the shoulders. A dead dog lying on its side, bloated in a muddy puddle on the side of the road. A family packed into a truck, a mesh metal box hitched to the back with two dogs inside.

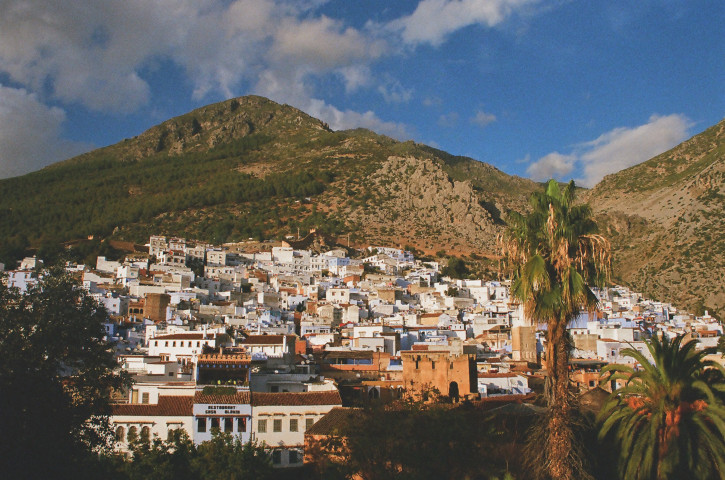

Night fell in the Rif Mountains. We passed a broken down bus on a blind curve. It started to rain. Our first glimpse of Chefchaouen was in that sparkling darkness, from on high, just lights in the valley. But when I think of it I imagine our last view, from the same position, in the morning, washed blue in the sun. The blue is from the European refugees of the 15th century. The Jews painted their buildings blue to remind them of God’s power. There are no more Jews in Chefchaouen but it is still blue.

We hiked to the ruined mosque, stark white against the brown mountain. The Spanish built it for the locals, but it doesn’t face Mecca and has never been used for Muslim prayers. Just another place to take a nice picture. Chefchaouen is a town of vistas and vantage points, every direction more beautiful than the last.

On the way down the mountain we stopped at a waterfall where local women were washing clothes. I pointed my camera at a little girl and she gave me a dirty look.

We bought a beautiful cactus fiber carpet from a man named Abdul. He gave us a Moroccan proverb: There are two mountains, but they never meet. It is we who must move.

At a hotel bar, one of two places to get a beer in town, we encountered a group of backpackers at the beginning of their journey. They exchanged stories, told us of Fez, which we never saw. They were excited, wondering where and how to buy drugs. We told them about our time in the south, of Marrakech and the coast, but left after a round. There is a feeling you get near the end of a trip, with all your clothes dirty and hungry for food from your own kitchen, when you start making a list of all the things you want to do or be when you return home. In some ways a reflection of how the trip has changed you.

We drove back to Rabat, entering the city as if we knew it, as if reprieved. We spent the evening with our friend Amine. He and Ben ate brothy street escargot. Amine kept calling the snails snakes.

“Death is always on the way, but the fact that you don’t know when it will arrive seems to take away from the finiteness of life. It’s that terrible precision that we hate so much. But because we don’t know, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that’s so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.” — Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky

Chefchaouen, Morocco

October 2012