There is nothing in the desert, and no man needs nothing. — Lawrence of Arabia

Salah greeted me outside my hotel, wearing a small, brownish turban, a leather jacket and a thick, black mustache. Sleep deprived and fever addled, I half-expected him to brandish a sword from a scabbard (I had spent several hours the night before in the hotel bar, watching Lawrence of Arabia, which played for guests every other night. Off nights was Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade). Instead, he led me to his silver RAV4, where the tape deck played Jordanian pop music and he told me about his tourism business, indicating the photo albums at my feet. Pictures of him with pasty Englishmen in waterfalls, floating effortlessly in the Dead Sea, camping with Bedouin in the desert. “That’s where we go now,” he said to me.

We drove through Wadi Mousa, the unfinished homes built on hills growing fewer and fewer as we descended to a flat desert valley. Mountains loomed in the distance like storm clouds. Salah left the paved road for the sand, picking his way from path to path in an unknowable pattern, like a scout tracking its prey. We wound through the endless open desert; I had no idea where we were headed. There was nothing. And then suddenly, there was a camp, black against the dusty expanse. Salah pulled up to one tent, not too close, and we got out.

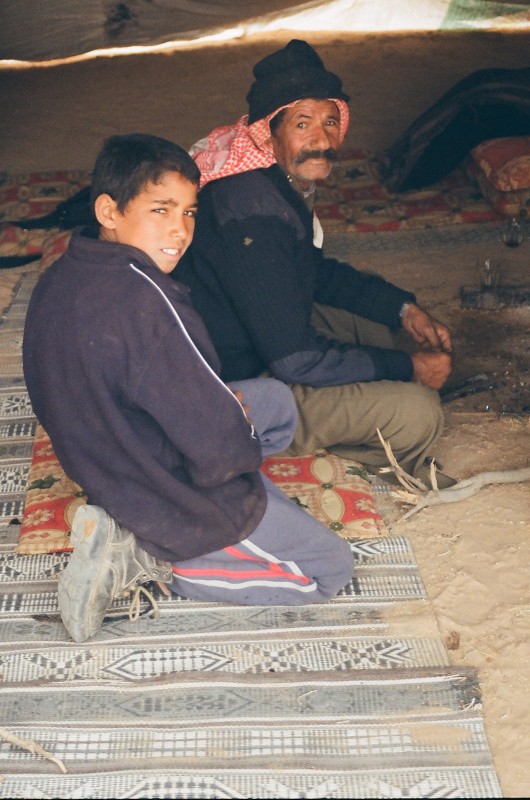

The home of Salah’s friend Ali consisted of two large rectangular tents of woven goat hair, a wooden outhouse, and a goat shack, with several black and white goats roaming around. A camel was tethered in the sand nearby. Ali had fourteen children, but only one son. His daughters and wife were in the other tent; they never came out while we were there. Salah told me that in the thirteen years he’s known Ali, he has never seen any of his daughters or his wife. Ali’s young son Jazzy, dressed in embellished jeans and a polo shirt, led us behind the tents to show us the goats and camel, but the wind was whipping and fierce with sand, so we went back to the tent.

I had been sick with strep throat and Ali made me tea with a mixture of 40 herbs that he grows himself. It tasted spicy and sweet and thick with chunks of the herbal mixture. The tea soothed my throat, but not permanently, so Ali crushed an aspirin into my next cup of tea, the result of which was far less enjoyable. He cooked for us a lunch of kebabs in the fire pit near the entrance of his tent. He said his tents have burned down before, but they keep goats, so they can weave a new one. The tent stretched off far to my left and was swallowed in darkness. It was so large that I thought Ali’s daughters could be sleeping back there and we wouldn’t know it.

After lunch, Jazzy brought Ali his homemade rababah and he played for us that eerie, minimal music while we drank more tea. Ali was proud of a collection of business cards he had from other tourists that Salah had brought to meet him. He showed me this collection and watched with pride as I recognized place names, but he wasn’t surprised, or shocked as I was, to find a card from a Jewish couple, last name Levy, from the small town outside of Chicago where I was raised. The card was worn, maybe the Levys no longer lived there, like my family. But it was a powerful talisman to hold in the middle of the desert on the other side of the world.

“and what relation was there between the so-called monuments of the past and the vague longing, propagated through our bodies, to people the dust-blown expanses and tidal plains of the future.” W.G. Sebald, Vertigo

It’s not called the valley of the moon for nothing. It has been used as a filming location, often as another planet (most recently in Prometheus). The desert is always otherworldly, but Wadi Rum is especially Martian, with its steep and jagged cliffs and everything in shades of red. The overcast weather, with intermittent sun streaming in plaits through the clouds, compounded the effect. I felt not far from home, but far from earth. It’s interesting that we think of Earth as somehow separate from the solar system it’s a part of; seeing this land and its lunar-like surface reminds me that it is just another planet, the one we live on. This, too, is outer space.

Salah seemed to know the terrain like the back of his hand. He shuttled us from one majestic rock monument to another, never looking back, always certain of his way. As we got further into it, I felt a loosening grip on reality, a certainty that I would never make it back. There was no road anymore and the vastness felt claustrophobic. At one point Salah pointed out my window at a camp simliar to Ali’s, though this one seemed even more remote, possibly because they weren’t Salah’s friends and we hadn’t eaten lunch there.

We came upon a dune that ended abruptly in a steep fall, affording us a lookout. Without warning, Salah tipped the Toyota over the dune and we sledded down the embankment, stopping just short of the mountain wall in front of us. It took some jimmying to get out of the position, nose to the wall, rear up the sand dune, but he did it, and we continued racing through the desert, red sand flying, the car jumping over stones.

The tether that I had left behind in the world was growing longer and longer, close to snapping, I thought, when suddenly, street signs appeared, a gas station, a mosque, a highway. I turned in my seat to catch a last glimpse of the desert, its rocks on fire in the sunset.